Monica Hesse on writing historical fiction for young readers

If you’re like me, you’ve spent a lot of the past two months daydreaming of “After.” After covid-19, after quarantine, after stay-at-home orders, after exhausted-looking nurses begging for more personal protective equipment on CNN.

After, I’d like to go to a crowded movie theater and order buttered popcorn. I’d like to hug my best friend; she’s pregnant and she informs me over the phone that she’s increased in size from Pluto to Jupiter. I have a long wish list, but sometimes its hard to imagine the world ever going fully back to normal. Some things are just too wounded. Recovery will be its own journey in ways big and small; it’s going to be a long time until I don’t marvel at a fully-stocked toilet paper aisle.

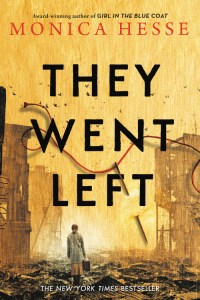

My latest novel, They Went Left, is set in Poland and Germany in the months immediately following World War II. It’s about the concept of “After,” when that concept turns out to be so more complicated than anyone expected. “What did they mean, it was over?” my main character, 18-year-old Zofia Lederman thinks to herself as her liberators celebrate V-Day. “I was miles from home and I didn’t own so much as my shoes. How was any of this over?” Most of Zofia’s family was killed at Auschwitz-Birkenau, and now she must set off on a quest to find her only living relative, her younger brother, Abek.

I chose this time period and this setting because I realized that in my five years spent researching World War II, almost everything I’d read ended in 1945. But that’s where I wanted my story to begin.

They Went Left isn’t a story of a continent falling apart. It’s a story of a continent putting itself back together. And more specifically, it’s the story of one young person learning about her own strength and resilience, coming to terms with her past and forgiving herself for what she had to do to survive. It’s about family, and how sometimes it doesn’t look like you’d expect it to, and it’s about life, and how sometimes there is no option other than to move forward.

Zofia eventually travels to a refugee camp in Germany, where she meets a young woman who is engaged a man she’s only just met. Breine tells Zofia that her previous fiancé died before they could have their wedding, so she is now “choosing to love” the man in front of her. They Went Left is about choosing to love: accepting that we often don’t have control over the terrible things that happen to us, but we can choose to find moments of beauty and kindness in their murky aftermath.

And, did I mention it’s also a love story? Did I mention it’s also a mystery?

I’ve had a lot of interviewers ask me recently, “Why World War II?” This is my third book set in that time period: Girl in the Blue Coat was set in occupied Holland in 1943, and The War Outside was set in a Texas internment camp in 1944.

I think I keep returning to this time period because it represents the very best and worst of humanity, and all the moral gray area in between. On the same residential block, you could have one neighbor risking his life to hide a Jewish family, another neighbor reporting Jews to the Nazis—and a third, just trying to ignore the entire occupation and make sure his own children had enough bread. I’m always interested in those stories: when the world around you has gone mad, how do you decide what it means to do the right thing? What kind of person do you become?

Those questions are particularly important for younger readers, in the middle of shaping their own world views. What I love about historical fiction is that the books give those readers a safe space to ask and answer those questions. Reading about a young black market worker in Holland allows teenagers to debate what is ethically acceptable in times of turmoil. Talking about the internment of Japanese-Americans in WWII allows readers to sort though questions of liberty, patriotism and xenophobia, without ever mentioning the terms “Republican” or “Democrat.” Among many things, books can be tools to help us develop our own moral compasses. They can help us realize that the problems of today are actually human problems, experienced and solved over and over again through time.

As for me, right now I’m taking a lot of comfort in reading and thinking about the lives of my characters, and the lives of the real people rebuilding their lives in 1945 and 1946. In circumstances far more horrific than I’ll ever know, they found hope, and community, and togetherness. They found an after.

Until we can all return to a semblance of normalcy, I hope you can also find some comfort and community in reading. If we can’t be in the same room, we can at least be on the same page.

But the deeper Zofia digs, the more impossible her search seems. How can she find one boy in a sea of the missing?